Written by Henry Hoffman, MS, OTR/L

Written by Henry Hoffman, MS, OTR/L

Shoulder pain resulting from stroke hemiplegia is a common clinical consequence. Hemiplegic shoulder pain can occur as early as 2 weeks post-stroke but an onset of 2 to 3 months is more typical. Frozen shoulder, pain, and weakness can negatively affect rehabilitation outcomes as good shoulder function is a prerequisite for successful transfers, maintaining balance, effective hand function, and performing activities of daily living (ADL).

If you are an Occupational Therapist reading this, you will want to sign up for the new CEU on this topic Stroke Shoulder Simplified: Demystifying subluxation, pain, and stiffness.

Licensed occupational and physical therapists must be knowledgeable in understanding the biomechanics and pathomechanics of the shoulder complex in order to properly examine and treat patients at the level they deserve. Regardless of the orthopedic or neurologic diagnosis, subacromial pathologies are the same. Yes, the causal factors may be different, but mechanics are mechanics and lesion sites are lesion sites despite the pathogenesis.

The purpose of this article is to offer an introductory review of the bio- and pathomechanics of the glenohumeral joint and scapulothoracic articulation. By developing a better understanding of the shoulder, we as clinicians will be more suited to resolve the functional limitations of our clients and offer them an improved quality of life.

Table of Contents |

Arm elevation is the most important function of the shoulder. There are 3 types of arm elevation: flexion, abduction, and scaption (plane of the scapula). In order to perform full arm elevation, the glenohumeral, scapulothoracic (articulation), sternoclavicular, and acromioclavicular joints along with the cervico-thoracic junction have to participate in a coordinated, concomitant, and smooth pattern.

Normal maximum shoulder elevation is 180 degrees. Traditional theorists feel the overall glenohumeral-scapulothoracic rhythm is a 2:1 ratio. Recent literature now suggests that the 2:1 ratio is not consistent across an entire arc of shoulder elevation. The first 30-60 degrees of elevation has been termed the setting phase. The scapula is seeking a position of stability in relation to the humerus during this phase. As the arm elevates, the scapula has the tendency to tip secondary to the weight. To prevent this, the trapezius and serratus anterior contract to stabilize the scapula. In addition, these 2 muscles combine to form a force couple that upwardly rotates the scapula. In this early phase, motion occurs primarily at the GHJ.

Note: Poppen and Walker report a 4:1 glenohumeral to scapulothoracic ratio during the first 25 degrees, thereafter, an almost equal 5:4 ratio occurs. Doody showed a 7:1 ratio during the first 30 degrees, thereafter, a 1:1 ratio from 90-150.

In the middle 60 degrees, elevation phase, glenohumeral motion is about equal to scapulothoracic motion. In the last 60 degrees, glenohumeral motion is again more than scapulothoracic motion (5:1). The final scapular motion is the result of clavicular rotation and elevation of the acromioclavicular joint.

Movement at the scapulothoracic articulation is important for normal biomechanics of the shoulder joint. Scapulothoracic rhythm is important because it (1) sets the most functional position of the GHJ, (2) prevents active insufficiency of the scapulohumeral muscles, and (3) allows for sufficient ROM between the humeral head and the subacromial space.

The glenoid fossa and the humeral head are incongruent surfaces. Rotation of the joint cannot take place as a pure spin but requires that the motions of the humerus be accompanied by a combined rolling and gliding of the humeral head on the glenoid fossa in a direction opposite of the movement of the shaft of the humerus. The humeral head slides posteriorly and inferiorly in flexion, anteriorly & superiorly in extension, inferiorly in abduction, and superiorly in adduction. In external rotation, the humeral head slides anteriorly and in internal rotation, it slides posteriorly.

The largest and most important glenohumeral muscle. As the humerus elevates, the translatory component of the deltoid as a whole increase joint compression. When the humerus is in the plane of the scapula, the anterior and middle deltoid is optimally aligned to produce elevation of the humerus. In this motion, the posterior deltoid primarily serves as a joint compressor.

The primary function of this muscle is abduction with the secondary motion being external rotation. It exerts maximum effort at approximately 30 degrees of abduction. The secondary functions of the supraspinatus are to compress the GHJ and to provide stability at the humerus during elevation.

The function of these muscles is to depress the humeral head and prevent superior impaction of the humeral head into the acromion. In addition, they provide muscular balance and help stabilize the joint capsule.

Latest EMG studies are showing that during arm elevation, the above muscles are acting as humeral head depressors. In addition, the muscles function as stabilizers for the anterior capsule.

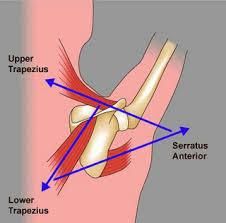

These muscles form a force couple that drives the scapula into upward rotation. In elevation, the force of the trapezius is more critical to the movement of upward rotation than the force of the serratus anterior. However, in order to perform full elevation both of these muscles must be firing.

Prior to and following an orthopedic injury to the shoulder, pathologic changes take place. Because of this, the normal mechanical behavior of the shoulder is substituted with asynchronous and faulty mechanics. Following a neurological injury (UMN lesion) damage to the sensory and motor areas of the cerebral cortex and brain stem may lead to primary impairments such as weakness, motor control, sensation, and tone. These clients often suffer from paralysis or abnormal tone in the muscles controlling their glenohumeral joint and scapula resulting in poor biomechanics which can lead to micro-traumatic lesions. Therefore, an orthopedic or neurologic injury can cause the entire upper quadrant elevation chain to be affected.

When poor mechanics or soft tissue lesions are present, it is the clinician’s job to identify the source so proper treatment strategies can be provided. Below are examples of some of the common shoulder pathologies seen by orthopedic and neurologic clients:

1. Subacromial Impingement – involves painful compression of one of the soft tissue structures located between the head of the humerus and the acromion, coracoacromial ligament, coracoid process, or AC joint. Impingement may occur due to structural narrowing (primary) or from underlying instability of the glenohumeral joint (secondary). Biomechanical changes after a neurological injury place affected clients at greater risk for impingement.

Note: Soft tissue structures that can be impinged:

2. Tensile Failure – a repetitive eccentric overload of the rotator cuff muscles.

3. Internal Impingement – impingement of the soft tissues of the rotator cuff and joint capsule on the glenoid or between the glenoid and the humerus (i.e., overhead athlete).

Capsuloligamentous Injuries: result in partial separation of the humerus from the glenoid fossa. The rotator cuff is the primary stabilizing factor during mid-range motions. At end-range motions, the capsular ligaments become the stabilizing force. It is common for clients that performed repetitive overhead tasks to develop instability due to challenging the integrity of the ligaments. In addition, paralysis of the shoulder girdle due to a neurological injury may comprise the dynamic stability of the cuff muscles leading to an unstable joint.

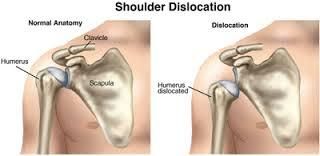

The most common type of instability (subluxation) associated with hemiplegia is in an inferior direction. Inferior subluxations occur when muscle weakness leads to a downward rotation of the scapula in relation to the thorax. The labrum and inferior portion of the glenoid fossa can no longer provide sufficient support to secure the humeral head into the glenoid. In addition to the faulty mechanics at the scapula, the proximal migrators of the shoulder (deltoids) are no longer able to support the weight of the arm. Gravitational forces applied to the weakened arm stretch the inert and non-inert structures to the point that the humeral head migrates distally below the glenoid fossa..

Capsular pattern is synonymous with frozen shoulder, immobilization arthritis, and adhesive capsulitis. It consists of a greater limitation of external rotation than abduction and a greater limitation of abduction than internal rotation, in a ratio of 3:2:1, respectively. Hemiparetic patients with limited movement often develop a capsular pattern (and pain) due to progressive adaptive changes to the collagen. Loss of motion occurs from the thickening and contracture of the coracohumeral ligaments and rotator interval which prevents external rotation. As the pathology progresses, abduction and internal rotation are eventually affected as well.

It is not uncommon for neurological clients to report a painful shoulder while in therapy. For moderate to severely impaired clients who are unable to raise their arm mid-range or higher, pain may result from spasticity and contractures. For mildly impaired clients that exhibit overhead active motion, pain may be due to compressive forces – primary or secondary impingement. This can come from the mild weakness of the scapular or rotator cuff muscles or instability due to a previous subluxation event that resolved itself.

Although the above clinical pathologies are not inclusive, it does reflect some of the more commonly seen concerns in the clinic. Understanding the biomechanics and pathomechanics of the shoulder is paramount for proper musculoskeletal management. Clients suffering from an upper motor neuron lesion, with passive or active movement limitations will have some degree of pathomechanical issues. Therefore, clinicians must understand how the entire kinetic chain operates as a complete unit in order to improve upper limb function.

If you are a clinician who mainly treats neurologically impaired clients, I encourage you to seek out orthopedic-based continuing education courses to enhance your clinical assessment and treatment skills. The added value of having a good understanding of the musculoskeletal system can be extremely significant when treating neurological clients suffering from joint pathology.

Check out Stroke Shoulder Simplified: Demystifying subluxation, pain, and stiffness to get started!

Interested in reading more? Review all Stroke Recovery articles and Stroke Recovery products.

Henry is known as a purveyor of neuroplasticity-based treatment and co-founder of Saebo, a leading provider of novel and evidence-based stroke recovery solutions. For over 20 years, he has provided hundreds of national and international brain injury/stroke courses certifying thousands of occupational and physical therapists worldwide.

Henry’s first stroke product, the SaeboFlex, was placed on permanent public display at the Wellcome Medicine Galleries exhibit at the Science Museum in London. The SaeboFlex was alongside other medical breakthrough technologies spanning the last 500 years, including the first MRI machine and the penicillin mold.

Saebo’s tagline is “No Plateau in Sight” with the understanding that there is no expiration date on neuroplasticity. Henry believes that patients can continue to make gains many years post-stroke and live a happy, healthy, and more independent life.